A Reflection, Book Review of Asian Honor, and Further Reading Resources

Caveat Lector

I don’t know who you are, but I tried to imagine my audience before writing this. I don’t want to treat you like you’re an indistinguishable person from a large bloc that self-identifies as Chinese. You’re likely a hyphenated Chinese, for one. Singaporean Chinese. Or Chinese-American. Or another category of Asian, not Chinese. Or you could be hilariously devoid of yellow and brown and just enjoy my ranty blog posts (one can dream).

I want to think that you’re going to be sympathetic to what I write here. But also consider this a content warning that I’m not going to be sympathetic to the “core” of Chinese culture, which is its obsession with “face”.

I believe the entire concept around face (the worry about one’s social reputation and standing, and appearing free of fault) undermines mental health and stands in opposition to healthy self-worth and self-actualisation.

Face, or mianzi, has been romanticised by Hollywood as “honour” but demands conformity and compliance, and masks insecurity, narcissism, and systems of control. Of course it has pride of place in a neurotic, authoritarian and conservative culture. Face protects bullies and enablers. It protects the status quo. Face silences the whistle-blowers and voices of discontent.

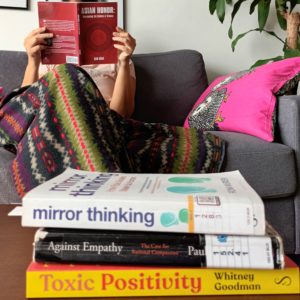

I started writing this as a review of one book about Chinese shame and mental health. But to be honest, I wanted more books. I wanted more stories, too. Because I wanted to find other people who’ve been chafing, like me, at the emotionally destructive conditioning we inherited.

Asian Honor: Being reviewed in this post

Mirror Thinking: Not bad, jumps off the latest science about mirror neurons and how role models impact us in early and adult life. Found it personally triggering but well argued.

Against Empathy: Slippery reasoning, and I gave up.

Toxic Positivity: Not started yet, but I follow @sitwithwhit on IG.

For myself, I’m Singaporean Chinese born and raised, but “watered” down with Peranakan blood from my mother’s side. Chinese Peranakans, as the story goes, are mostly descended from the Chinese contingent that accompanied Ming Dynasty princess Hang Li Po to Malacca in the 15th century. No records on both sides of the family so I can’t confirm anything. The grandparents on both sides had no education or big financial legacy. By Crazy Rich Asian standards, my Chinese Peranakan heritage would appear unusually lowly.

My father’s side comes from Hong Kong.

I’ve also lived in the US as a student and green card holder (card long expired). I’m decidedly a child of British colonialism, yet happy that an English-language education gave me the tools and vocabulary to understand my own humanity. Meanwhile my Chinese language teachers (with only one exception) gave me grief, propaganda, prejudice, and trauma. It seemed I was never submissive, compliant, or Chinese enough to please them. I’m sure they thought everything they did was for my benefit. But till today, I think none of them should have been allowed near pedagogy.

I’m really not joking.

Sidebar on the Chinese Language and Janet’s Schooling Years

(Link to skip this section and get to the book.)

This may not be exclusive to Chinese culture, but when I was growing up, there seemed to be no effort from my authority figures to understand the emotional development of children, nor to explore different approaches to teaching, beyond repetitive drills, memorisation and regurgitation. To bookend these exciting pedagogy methods, along with crushing homework, my Chinese teachers loved meting punishment by humiliation, yelling, and throwing your own work at you.

I tried. I read my Chinese textbooks over and over, to commit new words to memory. I painstakingly read extracurricular books with the help of unhelpful Chinese dictionaries (this was before Internet and electronic dictionaries). But all the time, energy and private tuition invested never actually helped me get better grades in Mandarin. I cried a lot–in secret, duh–because of the abusive Chinese teachers and the fear of failing school because of Chinese. (I consistently got top or above average marks in my other subjects.).

It was a constant failure. This was me at my most traumatised, helpless, despairing, and ashamed. No matter what I did, I sucked in the language, and it wasn’t for lack of desire to do better. I got no sympathy anywhere. I just kept being told I wasn’t wanting it, which was untrue. But the more I failed to get better grades, the more I hated myself, my life, my teachers, school, Chinese people, the entire Singapore education system; LKY (the holy father founder of Singapore’s language policies); and my parents. I begged for them to migrate somewhere, anywhere, I wouldn’t have to study, and be tested, in this godforsaken subject. I found most Chinese language media shallow, sensationalistic, and puerile; and would have been in bliss if I could be left alone to read pulp science fiction and fantasy novels.

Call me fully colonised, but what I absolutely hated was to be told by condescending educators that Chinese was my “mother tongue”. It wasn’t–neither of my parents spoke Mandarin Chinese because neither were born into that language. They spoke dialects and different dialects from each other. Their common language was English.

Somehow I made it to junior college anyway, and white-knuckled a shameful but ultimately passing grade in the Chinese language. The day I realised I didn’t have to study it anymore; I felt more relief and happiness than when getting married or becoming a mother. I know it may “look bad” to admit my happiness might have peaked at 16 years of age and over a grade, but that’s how much trauma I’d gotten from being forced into mandatory Chinese classes by my Singaporean education.

Not a great show for my relationship to Chinese culture, you could say. My experiences with abusive Chinese teachers and the system might have given me an ax to grind, you could say.

Well, yeah. It was traumatic stuff for me, and I wish that the younger me and others like myself, rare as they may be, could have been spared. And I’m inclined to think that anyone who disagrees is either a psychopath, or possibly worse, a Chinese language teacher.

Asian Honor: Overcoming the Culture of Silence

If there’s another thing I grew up with, it’s the eternal anxiety that I could do something that made my family “look bad”. “Don’t make us look bad,” “this makes us look bad,” and “this looks bad” was the most common urgent whispers I heard while navigating the spaces with extended family and other Chinese people. (Face was also the reason why I was told I had to study Chinese.)

At first, I kept asking why or how I could make things “look bad” when my intentions were completely innocent. No, I didn’t want the food offered me, nor did I always feel like greeting some relatives. But I would be told to comply to “give face”. If I brought up the issue again later (in private), the common answer given was that swallowing and denying my own wants was virtuous; I had to “show respect,” especially to older people, strangers, and tradition. Doing otherwise “looked bad”. This was unsatisfactory and glaringly one-sided to me. I was never convinced. This reached its peak (or nadir) when I was told that crying as hard as I was at my brother’s funeral “looked bad”.

But I gained bitter clarity: Negative emotions, and even personal challenges, were never to be shared nor shown–not even at a sibling’s funeral, apparently. I’m sure it “looked bad” when I had to be taught this at the age of 32. Since then, I have intermittently searched for material on face and shame in Chinese culture, and how these have impacted mental health.

Enter Sam Louie’s book. Its first lines were these:

“Asian cultures are rooted in shame. We are known as shame-based cultures since our lives, families, and mindsets revolve around some aspect of shame. Our identities are forged by upholding our honor while trying to avoid any shame-producing feelings, thoughts, or beliefs. Few are able to break the cultural shame that binds them. Instead, they suffer in silence.”

My partner watched me madly underlining and writing in the book in the few days it took to read and finish. I connected strongly to almost everything that was described in it; how we wall off our feelings and try to maintain false selves to please family and community, many of us ultimately choosing to suppress our emotional sides, and often feeling shame for having emotions at all–especially the negative and stigmatised ones such as rage, grief, helplessness, envy, sadness, fear and sexual desire.

The avoidance of emotion–showing it, articulating it, understanding it, or processing it–ultimately makes authenticity and emotional intimacy all but impossible. When we’re forbidden to acknowledge our emotions and vulnerability for fear of “losing face”, we can stew in shame and self-hatred–just for being human. Worse, we can project our un-owned stuff onto others. A lot of energy goes into maintaining the mask, in a desperate bid to stave off the feeling that if we don’t, we’re flawed, unworthy, and unlovable.

In a nutshell, those in this culture can be starved for unconditional acceptance and emotional outlet. Louie’s short book covers shame in Asian culture (to be read as East Asian) and how it affects other parts of Asian life and culture, including our sense of pride or “honor” (American spelling, bear with), our attitudes to suicide, family dysfunction, addiction, sexuality, masculinity, processing our childhood, seeking help and recovering from addiction.

This is a 10 year-old book, but the ever-prevalent “face” and fear of looking bad has persisted in Chinese and East Asian culture so long that it reads as timeless. Louie’s sharing of his own experiences with shame and addiction were open, honest and refreshing–in a way that I’ve found rare when Asian authors write their backstories for self-help or coaching literature–the low points in their journeys often come across as shallow or shellacked to avoid, heh, looking bad. So I appreciated Louie’s courage and candour, especially in breaking the silence with his own examples.

One, that I found myself double-highlighting, was Louie’s experience of lacking parental affection and interest in what he wanted to do with his own life. (Children not only want to be seen for who they are, they also crave physical touch–brain development and emotional regulation cannot be fully realised without it.) I loved Louie’s telling of how he sought his mother’s touch as a child, and was so rarely, meaningfully touched or hugged that receiving his mother’s hug on his wedding day brought on tears–and the later realisation that the reaction was actually sadness over a lifetime starved of this.

I suspect both Louie and I experienced what I observed: That in Chinese culture, needing or wanting physical affection was treated as shameful and childish, that public and physical displays of affection were often considered ill-mannered, low, and uncouth.

Examples from my own life are many. One of my Chinese language teachers had been an ancient and crotchety photography enthusiast, prone to ranting to his unfortunate captive audience. We sat through at least one long tirade on how the immoral and degenerate West was ruining society with movie/TV kissing scenes. I’d seen the same embarrassment and aversion in my own mother to affection and sexuality on screen. I’d grown up and listened to little Asian aunties in the market admonishing new parents not to spoil children with too much praise and affection. Public displays of affection in the 80s and 90s were viewed with disgust and elders commenting that the offenders’ parents had not taught them shame.

(In my own life, I internalised that relationships in general were as contemptible as physical affection. It was always a panic-inducing thing to tell my parents when I was dating anyone. No matter what, there was the feeling that I was failing by not getting a good-enough boyfriend, or to admit that someone was showing me affection, worse, that I might be showing anyone ew icky feelings ew, and surely I was being sullied by being in a relationship at all. I saw more contempt than affection between my parents, and all these things together primed me for dismissive avoidant attachments, if not abusive relationships.)

If Encanto had been Asian

“During my childhood, I don’t recall ever having a conversation or being able to tell my parents when I felt anxious, scared, confused, angry, disappointed, or hurt. What was unconsciously ingrained in me was that it was not permissible to hurt, so when I did hurt, I just buried those feelings.” (Louie, pg. 51)

Louie goes some depth into addiction and sex addiction; this was something he navigated himself while working in Journalism and before transitioning into psychotherapy. His lens is also that of a Christian who leans into his faith during his challenges, and while putting together how his childhood experiences shaped his adult search for intimacy and self-worth. He puts together a compelling argument about how toxic shame, built up from a childhood of emotional deprivation, leads to compensatory and addictive behaviors, with the eye-opening statistic that 88% of addicts come from disengaged families.

(This statistic is from 1991 and Dr. Patrick Carnes; seen in context with the rise of screen addiction and social media addiction, it has kinda sobering implications.)

Addiction and mental health in Asian culture also comes up against overwhelming stigma even today, with many viewing mental illness as a source of shame, a moral failing, a loss of face, and “fixable” only with punishment and/or ostracisation.

“Asians are found to have a lower sense of responsibility towards the mentally ill, as compared to respondents from the other ethnic groups. The concept of ‘face’ comes into play in this regard, as it deals with our moral standing in society.” Source

Chapter 11 in Louie’s book goes into how this moral judgment and grandstanding to maintain one’s superiority and mianzi wind up impacting our familial, romantic, and professional relationships. Trying our best to avoid shame and abandonment, we essentially learn codependence, the need to please and win the approval of others at the expense of our own wants and wellbeing. We find it difficult to admit difficulty or show vulnerability, we constantly feel “not good enough”; and indeed a lot of the motivation behind our actions becomes that of avoiding loss of face. We distance ourselves from our uncomfortable bits, and this has a knock-on effect on so many parts of our lives.

There was plenty in this book that I related to and enjoyed, but I have to admit less connection to the Christian bits in the last chapters. I was also a little sad (though this is no fault of Louie’s) that this book was the perspective of an Asian male. It’s a valuable perspective, but as an elder daughter (now singleton), it missed out on talking about the parentification I’ve found more common among Asian daughters than sons–particularly with the eldest daughter, and the extra shame and guilt we get trying to be perfect while carrying the emotional labor for both siblings and parents. Moreover, Asian women and daughters exist in a highly hierarchical and misogynistic context that deems us less valuable than the sons that will carry on the family name. (Perhaps this needs a female author and its own book.)

In the US, statistics continue to show the low rates at which Asian Americans (and Pacific Islanders) will seek mental health help. At same time, suicide is the leading cause of death for those in this ethnic group for ages 15 to of 24 (source). More recent and local statistics on Asian mental health within Asia continue to show the disheartening stigma against mental illness and those who suffer it, something I experienced in my own family.

Note: You can find Sam Louie at LouieAssociates.com, and purchase Asian Honor: Overcoming the Culture of Silence and pre-order My Passport to Shame: From Asian Immigrant to American Addict coming out in June 2022.

Conclusion, For Now

Asian Honor was a welcome read. It helped me feel less alone, and it was encouraging to see someone write so honestly about their own experiences, while including useful references and concepts about developmental needs, addiction, and relationships.

This is also a book some may dismiss because it’s easier to continue to claim addiction as a moral failing, and sex addiction as a sign of Western degeneracy. Denial and judgment, I’m sure, will remain easy habits for those who don’t want to look at their conditioning and assumptions too closely, much less to break down how so much Chinese culture has been pinned on authoritarianism, childism*, inauthenticity, shame, and masking.

*Childism here in the meaning defined by the late Elisabeth Young-Bruehl: “a prejudice against children on the ground that they are property and can (or even should) be controlled, enslaved, or removed to serve adult needs”.

To end, my “further reading” list below is long, but I doubt this will be the last time I visit this subject. Having lost a sibling to suicide by mental illness, and my anger at how much abuse and harmful traditions are normalised by “conservative cultures”, you’ll find other “f*ck Confucius” pieces in my blog. (I refuse to apologise about it.) I may have as much face to lose now as I have shame. Which perhaps isn’t a bad thing.

Cover photo: https://www.pexels.com/@alinari

Further Reading

- This Cultural Norm Affected My Mental Health as an Asian American With Chronic Illness

- Depression is why I’m writing this. Shame is why I’m writing it under a pseudonym

- How Asian Shame and Stigma Contribute to Suicide

- I Kept My Family’s Secret For Over 60 Years. Now, I’m Finally Telling The Truth.

- Mental Health Disparities: Diverse Populations

- Understanding and addressing mental health stigma in Asia

- Stigma among Singaporean youth: a cross-sectional study on adolescent attitudes towards serious mental illness and social tolerance in a multiethnic population

- Mental illness stigma’s reasons and determinants (MISReaD) among Singapore’s lay public – a qualitative inquiry

- Commentary: Isolated with your abuser? Why family violence seems to be on the rise during COVID-19 outbreak