Previous installment: Life After “Dead Inside” Part 2

My mother made it clear it was a curse to be born female. If I showed a differing opinion, she had life experience aplenty with which to beat me down.

Some of it hardly required her effort. My periods sucked. My cramps were awful, and I had other immune system issues, which were universally blamed on having womanly bits. I couldn’t even have good womanly bits (you’re getting only the best technical terms here), like bigger boobs and a finer bone structure and feet that fit in “f*ck me” shoes.

My mum was weird around a lot of things. Sex, sexiness, sexuality, sensuality, exposed skin and physical affection all embarrassed her, and not in a quiet, red-faced way. It was over-the-top shock and mortification, with loud condemnation for whoever dared to hint at sex, want it, or enjoy it. You couldn’t watch Paula Abdul dance on TV without my mother’s gasps and exclamations overpowering and making the entire experience excruciating. My mother drummed into me that “men are only after one thing” and women should never think to want it.

There are things I’m piecing together about her in hindsight. In “educational” moments she made sex sound like torture, and I don’t think it was just to scare me into chastity, though she did that too. I literally heard the “no man will marry the cow if he can get the milk free” spiel from her lips when I was around 10. Sex was shame. Sex was monstrous. Sex was the last bargaining chip you played only if you have no other choice.

The message didn’t change when I got older. It was baffling and maddening; we weren’t religious. By all accounts, my mother wore nothing but mini-skirts in her heyday and flexed that shit to score jobs and her driver’s license. Her extreme aversion to anything remotely sexual was inexplicable to my younger self. (Now, I can only fill in the blanks with tragic guesses.)

I didn’t share my mother’s squeamishness or shame around sex. I had books with sex scenes and I enjoyed them. But if anything, wanting affection or attention was the more shameful thing around my family. I learned to panic at any physical affection on-screen; you can guess how I reacted to it in meat-space. It was alien and harrowing. To me it often felt wrong and performative, as if it was only manipulation and prelude to sex. So you see, much as I fought my mum’s obvious stupidity around sex and pleasure, I still got fucked up.

I dreaded my birthdays. Some time in my teens, birthdays became the one awkward day a year my mother would hug and kiss me (on the cheek) in the morning. I would be in bed and couldn’t run. I couldn’t even remember her hugging me as a kid. Softness and affection just weren’t things to trust. They were weak, they were feminine; they were mocked by the other parent (and some relatives) for creating soft, spoiled people.

“Not Like Other Girls”

I learned early enough not to go to my parents for emotional validation or reassurance. What I didn’t know was that I would still seek it anyway, from others and from experiences that I could use to claim intellectual or cultural superiority.

The “solution”, again, was for me to pretend not to care about validation, admiration, connection, or affection. I still wanted a relationship to boost my social standing (why else–besides sex–did anyone suffer relationships, I wondered). Besides real life (which sucked), my education on sex and relationships came from books and media, some more questionable than others. The characters from Shirley Conran and Virginia Andrew’s books hardly made for good role models. The heroines from fantasy novels were not much better, though some of them had swords. Swords were cool.

1998, Kentucky. If I’d had a sword during this picture, I would have posed with it.

I had swallowed so much misogyny that I unironically believed the best woman was one who acted and thought like a man. Women were beautiful, yes, but everything inside them was wrong and feeling and weak.

The worst accusation you could have leveled at teenage Janet was of her being feminine. I eschewed make-up, pinks and pastels, princesses, kawaii toys, and pretty things. The dress above? Was a gift and had “historical”, cosplay and dramatic value. It wasn’t for being feminine. Capisce?

When I got into my twenties, I slowly allowed myself to look feminine (while still pretending not to care about it). Acting feminine was still a no-no. At least out in public.

Shadows & Soul Fragments

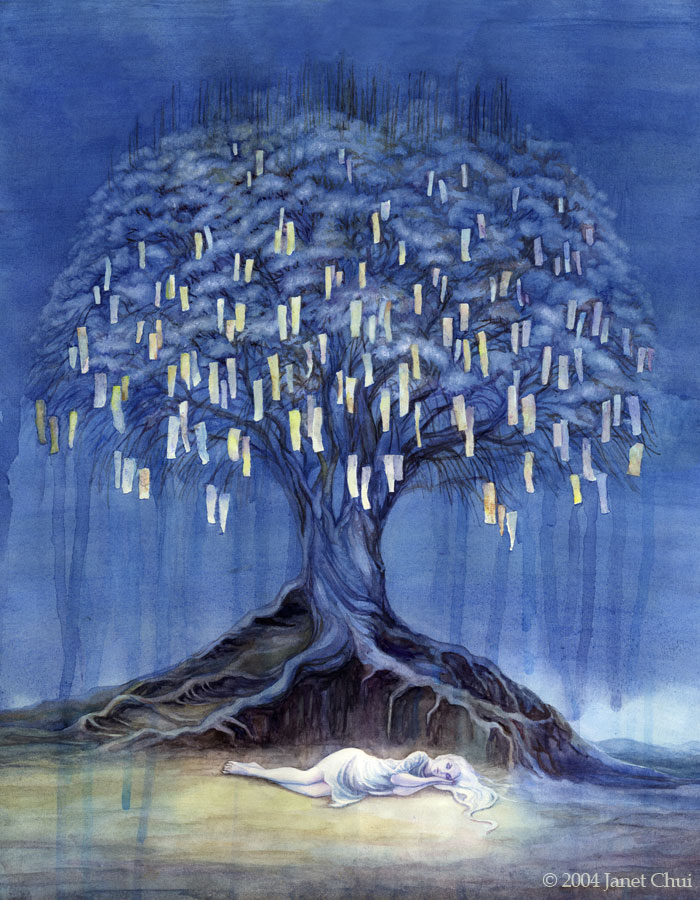

In the writing of this, I realise that I put my disowned femininity into my artwork. The women I painted were allowed to feel everything that I was not.

It means I hid them for TWO reasons:

- To escape the parent who called making art stupid

- To hide their emotions and femininity, because I could not safely admit they were also mine.

I could not admit that I wanted to be beautiful and brave. I could not admit that I felt isolated, sad, hopeless, and depressed. I could put these things into my paintings, but I also had to hide them, hide them, hide them. If I was caught, I had to say they were just what somebody else wanted and paid for. (Even that would be scoffed at and mocked.) Claiming the paintings showing shameful emotions or desires would only bring disaster. It was hard to predict what the Roulette Wheel of Parental Overreaction would bring: Panic and yelling? A crying parent and shaming that I caused their distress with my distress? Or maybe hours of being talked at to tell me that I was actually fine, maybe just oversensitive or paranoid like my brother. (We’ll get to that later. This is a lot of tragedy to pace.)

Easier to hide my work as much as I could, and hope my parents never looked at it on the Internet.

The Prayer Tree, 2004.

In the shamanic approach to healing, soul fragmentation and soul loss can happen when someone goes through extreme shock, trauma, or prolonged abuse. To quote:

Soul Loss can result in post traumatic stress disorder, gaps in memory, or feelings of “being spaced out” and unable to focus or concentrate. It can manifest as chronic depression, dissociation, immune deficiency problems, addictions, prolonged and severe grief or — in extreme cases — as suicidal tendencies or coma.

Alison Skelton

I set out to write this installment about how my upbringing fucked up shaped my ideas about femininity, sex, and sensuality. About being soft and feeling. The summary is this: I wasn’t allowed to be, and I didn’t feel safe. Some days I still don’t feel safe about it. But I can see that I put it into my art, and I wonder if this was my way of protecting and preserving my soul, without knowing it.

Title banner photographer credit: Ben Matchap.

(More is coming, but it may only go into the manuscript in progress. Make sure you’re subscribed for updates in case I put another excerpt onto my website.)